Over the last few weeks I have read a number of essays wherein a wide variety of authors make the case that American cities should adopt the transportation policies of exemplary European cities. One such essay is Chapter 6 of Timothy Beatley’s Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities, entitled “Bicycles: Low-tech Ecological Mobility.” In the chapter, Beatley argues extensively that American cities should build separated cycling infrastructure to encourage more people to bike, following the examples of cities such as Amsterdam, Münster, and København. He quotes Pucher,

The main reasons for differences in the level of bicycle use is public policy. In the US, very little has been done to promote bicycle use, … in the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland, by contrast, various levels of government have constructed extensive systems of bikeways and bike lanes with completely separate rights of way.

I am a cyclist, for recreation and transportation, and have been since I was about seven years old. I rode my bike to elementary school, high school, college, and now graduate school. I even remember flying through the streets of Ann Arbor on the back of my dad’s bike when he was in grad school. I lived car-free for two years as a missionary in Malaysia, and I’ve annoyed more than one store manager by asking him why his establishment didn’t have a bike rack. I love biking, and I want to have the best possible infrastructure to ride on. I am thrilled at the plans for the Beltline:

I feel that the Beltline will induce cycling trips among people who don’t normally ride bikes. My wife and I showed up at the Inman Park festival a couple of weeks ago on bikes, and the existence of the Beltline was a big factor in Leslie’s agreeing to that plan. We need to improve bicycling infrastructure for the safety of those who currently ride, and invite as many others to ride as well.

BUT: to claim that public policy and available infrastructure is the major difference, or even a significant difference, between American and European cities when it comes to cycling is absurd. It gets the direction of causality precisely backwards; European cities provide cycling infrastructure because people ride bikes, and not the other way around. The US became a primarily auto-oriented nation largely in the 1950’s and 60’s. Let’s look at GDP per capita over that time in the US and three northern European countries that are often cited as exemplary.

That difference is huge. The average US household was 2.6 times more wealthy than the average Dutch household in 1960. In the present, this ratio is the same as the difference between the US and the likes of Turkey, Chile, and Latvia. By the time these countries caught the US in the early eighties, the US had already completed the Interstate system, urban “white flight” was mostly over, and the transition to a suburban lifestyle was complete. It’s unfortunate that the World Bank data doesn’t go back through the 1940’s. What did the Netherlands economy look like in 1944? Oh, right…

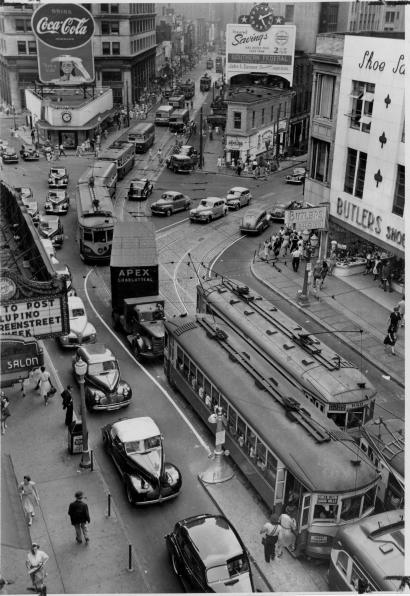

The Nijmegen-Arnhem region is not as large as Atlanta, but both cities are currently between the 7th and 10th largest towns in their country, depending on how you measure. What did downtown Atlanta look like at the same time?

Some urbanists would look at the Atlanta picture and say, “What a tragedy that we lost all of those streetcars!” I tend to agree with them, but that observation is largely beside the point, which is: Atlanta was rich. For the next thirty years, America could spend its enormous wealth building for a new future; the countries of northern Europe had to devote their limited resources simply to rebuilding their lives. And for better or worse, Americans in the middle of the century saw that new future as being centered on the automobile. The Dutch, meanwhile, started riding bikes because they could not afford cars. In an alternate history in which the brutal end of World War II had been fought along the Ohio rather than the Rhine, transportation planners in the low countries would be eyeing Pittsburgh and Cincinnati with severe jealousy. America’s auto-centrism is as much the result of historical accident and cold economics as it is the result of planning policy.

I have not even mentioned the topological and meteorological contrasts between Atlanta and Amsterdam. I don’t have hard data on this, but I know that no Dutch person rides their bike up anything like Piedmont Road 1in 95º weather and 95% humidity.2

In short, European cities have cycling infrastructure because people ride bikes. Will the Field of Dreams approach favored by some planners convince lots of Atlantans to start cycling for recreation and transportation? I really hope so. But we should not look to European cities as our examples, because any comparisons are false. We must make our own path, in our own way.

- Best thing about the Beltline being on an abandoned rail corridor? It’s flat. Like Holland. ↩

- Of course, climate isn’t always everything. ↩

Great post. I liked the point about what US cities and European cities were busy doing post WW2…growing vs rebuilding. And the photos provided really hammer that point home.

Very well made points – particularly interesting is the contrast shown in the 40s era when most of the countries were busy reconstructing in some form or the other and US was growing. Awesome!

I think issues related to biking are usually quite local (topology, climate, perceived social status,sprawl), so I fully agree that instead of making European cities our role model, we should try finding and addressing specific issues that are deterring people from biking here.

I appreciate Aditi’s description: “we should try finding and addressing specific issues that are deterring people from biking here”. As we come to understand the local barriers, however, we may well find that we can learn a lot from other places with existing, working bike infrastructure and culture.